Introduction

This is a summary of Deaton, Cartwright - Understanding and misunderstanding randomized controlled trials(Challenge 1 of Causal Inference).

Motivation

Randomized controlled trails (RCTs) are widely encouraged as the ideal methodology for causal inference. However, randomization does not equalize everything other than the treatment in the treatment and control groups, it does not automatically deliver a precise estimation of the average treatment effect(ATE), and it does not relieve us of the need to think about covariates. Above all, it cannot magically demonstrate causality with no prior knowledge or results from other methods. Thus, the authors intend to provide us with correct perspective about what RCTs are able to do and how should we use the results from RCTs.

RCTs Give Good Estimates of ATE

First, RCTs theoretically provide an unbiased average treatment effect while we cannot observe the individual treatment effects but only their mean. Besides, the unbiased estimate does not mean that variance is also low. Therefore, we need to make bias-variance trade-off in practical situation.

Second, warrant is required that there are no significant post-randomization correlates with the treatment and then we can conclude that an estimate is unbiased.

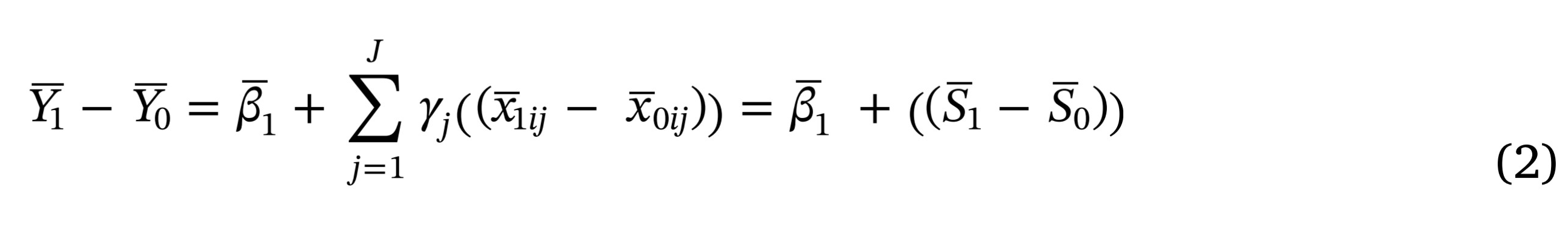

When the last term of the right hand side is zero, this is the case of perfect balance. With perfect balance, the difference between the two means is exactly equal to the treatment effects among the treated, so that we have the ultimate precision in that we know the truth in the trial sample.

Third, the inference problems cannot just be presumed away. When there is substantial heterogeneity, the ATE in the trial sample can be quite different from the ATE in the population of interest, even if the trial is randomly selected from that population.

Fourth, in many case the statistical inference will be fine, but serious attention should be given to the possibility that there are outliers in treatment effects, something that knowledge of the problem can suggest and where inspection of the marginal distributions of treatments and controls may be informative.

Using the results of RCTs

Suppose we have estimated an ATE from a well-conducted RCT on a trial sample. We thus have good warrant to make causal inference. But how and for what purposes to use the results?

The authors suggest that the use of RCT results is based on the observation that whether, and and in what ways, an RCT result is evidence depends on exactly what the hypothesis is for which the result is supposed to be evidence, and that what kinds of hypotheses these will be depends on the purposes to be served. And we shall distinguish a number of different purposes and discuss how and when, RCTs can serve them:

- simple extrapolation and simple generalization

- drawing lessons about the population enrolled in the trial

- extrapolation with adjustment

- estimating what happens if we scale up

- predicting the results of treatment on the individual

- building and testing theory

Following parts are based on above points and explained in a more detailed way.

Simple Extrapolation and Simple Generalization

Although extrapolation and generalization are sometimes reasonable, evidence from RCTs is not automatically simply generalizable and that its superior internal validity, if and when it exists, does not provide it with any unique invariance across context. Bertrand Russell’s chicken provides an excellent example of the limitations to simple extrapolation from repeated successful replication.

Support Factors

The operation of a cause generally requires the presence of support factors (also known as ‘interactive variables’ or ‘moderators’), factors without which a cause that produces the targeted effect in one place, even though it may be present and have the capacity to operate elsewhere, will remain latent and inoperative.

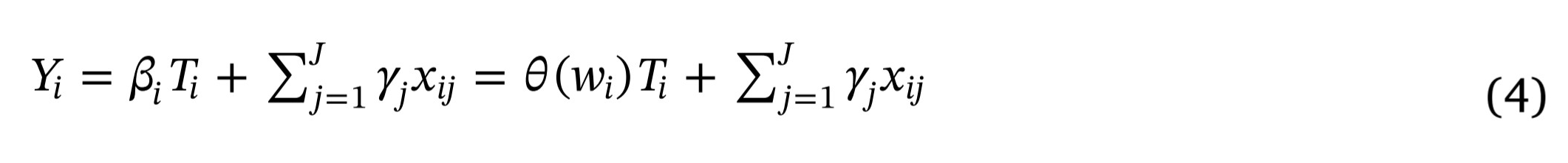

The value of the ATE depends on the distribution of the values of the ‘support factors’ necessary for T to contribute to Y. This becomes clear if we rewrite (1) in the form

Given that support factors will operate with different strengths and effectiveness in different places, it is not surprising that the size of the ATE differs from place to place.

Reweighting and Stratifying

Many advocates of RCTs understand that ‘what works’ needs to be qualified to ‘what works under which circumstances’ . Statistical approaches are also widely used to adjust the results from a trial population to predict those in a target population; these are designed to deal with the fact that treatment effects vary systematically with variations in the support factors. One procedure to deal with this is post-experimental stratification, which parallels post-survey stratification in sample surveys. The trial is broken up into subgroups that have the same combination of known, observable w’s (age, race, gender, comorbidities for example), then the ATEs within each of the subgroups are calculated, and then they are reassembled according to the configuration of w’s in the new context. However, these methods are often not applicable because we need to know more than the results of the RCT itself.

Using RCTs to Build and Test Theory

With well-established scientific claims, RCT results can be used in the familiar hypothetico-deductive way to test theory. For example, one of the largest and most technically impressive of the development RCTs is by Banerjee et al. (2015a), which tests a ‘graduation’ program designed to permanently lift extremely poor people from poverty by providing them with a gift of a productive asset. Thus, RCT successfully test the idea that this package of aid can help people break out of poverty traps in a way that would not be possible with one intervention at a time.

Scaling Up and Down

Many RCTs are small-scale and local, for example in a few schools, clinics, or farms in a particular geographic, cultural, socio-economic setting. If scaling up the population to the whole country or even the world, ATE we got in the original RCT may completely change. Just as there are issues with scaling-up, ATE for the trial population does not necessarily apply to each individual. Therefore, whether scaling up or down, we need to judiciously use theory and clearly identify the mechanism instead of simply applying ATE for large population or individuals.

Conclusions

RCTs are the ultimate in non-parametric estimation of average treatment effects in trial samples because they make so few assumptions about heterogeneity, causal structure, choice of variables, and functional form. But the credibility of the results, even internally, can be undermined by unbalanced covariates and by excessive heterogeneity in responses, especially when the distribution of effects is asymmetric, where inference on means can be hazardous. In short, we need to focus more on the underlying mechanism why things happen and RCTs are only the powerful tool we have.

Critique

The authors elaborate potential drawbacks of RCTs and realize that it is onerous in practice to cope with those drawbacks. They keep to remind people of focusing on underlying mechanism but provide few specific methods to make true causal inference base on RCTs.